All at sea with children’s behaviour

Why is it that whenever we mention children’s ‘behaviour’, the inference is that we’re talking about bad, or challenging behaviour? Yet anything at all that children (and adults) do- good, bad or otherwise, is behaviour.

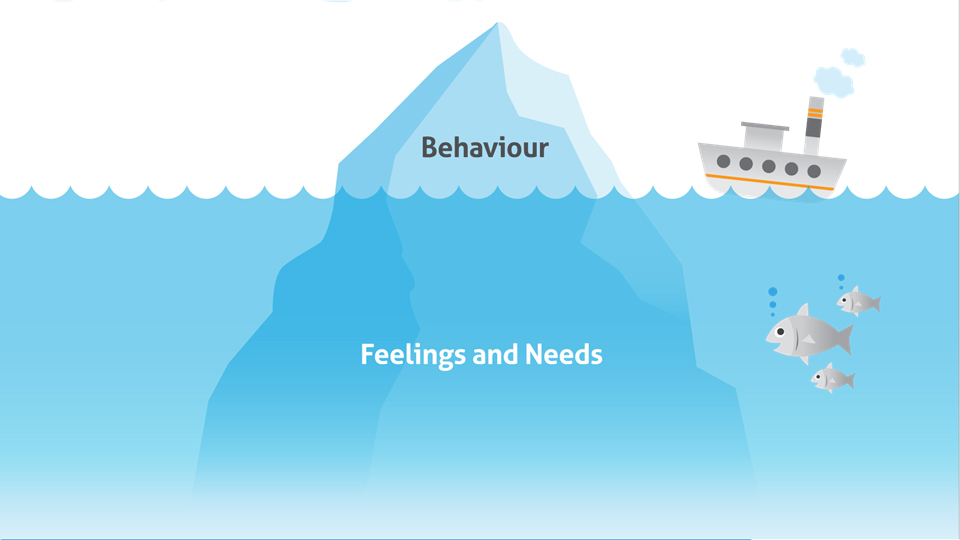

When discussing the behaviours of children with parents in our Bringing up Great Kids parent groups, we offer them a fresh way of viewing and thinking about what they see in children’s behaviours: our iceberg model of behaviour. This model acknowledges that all behaviour has meaning. The model positions behaviour as the tip of an iceberg, with all of the motivators for that behaviour lying beneath the surface. Important motivators of the behaviours of young children, include their needs and their feelings. Understanding that a particular behaviour won’t change unless its underlying needs and feelings are first acknowledged and understood, this model prompts parents to wonder about their child’s needs and feelings and to respond to those, rather than to the behaviour itself.

At times, the behaviours of young children can really press parents’ ‘buttons’. When that occurs, it is important for parents to reflect on their own needs and feelings, to avoid behaving in a way that harms children. (This is an ideal time to practise our STOP/PAUSE/PLAY routine!)

Issues around responding to behaviour are particularly pertinent for parents of toddlers. Between the ages of one and four, a child’s emotional brain centre is like a construction zone (or like your house, part-way throug

h renovations!). The ‘synaptic exuberance’ inside the child’s brain, manifests on the tip of the iceberg, with behaviours of easy frustration and strongly expressed feelings, which are so typical of toddlers. Beneath the surface lie the toddler’s big needs and very big feelings. Let’s look at a common example:

Two year old Archie wants the truck Jack is playing with. He grabs it from Jack. When Jack begins to cry, Archie hits him and starts to cry himself.

An adult carer who understands the iceberg model of behaviour would wonder about Archie’s needs and feelings (‘I need that toy and I need it now!’) and would then show Archie non-verbally, ‘I get you’. Staying with young children physically and emotionally when they are upset, lets them know that their feelings are understood and helps them to calm down.

Likewise, for Jack the carer’s role would be to think about what Jack might be feeling (‘Archie is mean/doesn’t like me’ or ‘but I really want that toy’), and then show Jack that they understand as well. In both cases, the most appropriate response might then be to give them both a hug.

Of course when we tap into children’s feelings this doesn’t mean we don’t set limits on their behaviour. But, in our experience (and this is backed up by current research) these limits are best learnt when children are emotionally calm. This is because the state of distress inhibits the brains ability to think clearly and to form long term memories. By taking the time to allow children to be supported in their feelings, we enable them to return to calm. Once calm, they are best positioned to learn & remember the lessons we might like to help them take on.

Learning to consider the underlying feelings and needs of children rather than instinctively respond to the behaviour on the surface can take time and practice. In our Bringing Up Great Kids groups we look at the differences between ages and developmental stages, considering what might be reasonable expectations on each child’s behaviour and their ability to manage their own emotions. We encourage parents to reflect on situations they’ve recently faced with their children and map their own icebergs to aid in understanding the feelings and needs their child might need support with.

Have you used a similar model with parents you work with?

What changes have you noticed in parents who build this type of skill?

For us, we have found that parents and children become more attuned or connected over time. Children increase their emotions literacy and better learn how to communicate their feelings in an age appropriate manner. These are terrific skills for any child to have, and together with the stronger relationship with their Mum, Dad or carer, will help strengthen their capacity to manage their emotions into the future.