Transforming Traumatised Children within Education – One School Counsellor’s Model for Practice

This article was authored by Deborah Costa, a registered psychologist and school counsellor with a professional area of interest and development in working to support traumatised children and young people in schools.

When we work as professionals supporting traumatised children and young people it is easy to imagine the possibilities schools can provide for them – to experience meaningful and satisfying relationships, feel internal and external safety and establish a sense of self and competency. These possibilities can develop within school-based experiences of belonging, connecting, relating, feeling, experiencing, dreaming, achieving, trusting and learning.

And yet, for traumatised students, the teachers they have, the executive members who support these teachers, and the Principal leading the school will ultimately determine how much of their schooling provides these meaningful, reparative experiences and opportunities for recovery and growth, and how much their damaging beliefs about themselves developed out of early life experiences of fear, rejection, abandonment, worthlessness, invisibility are reinforced and strengthened, intensifying the terror and hopelessness of their trauma experience.

The extent to which schools embed trauma informed practices and policies can influence both the educational and life experiences and accomplishments of students impacted by trauma. Schools are places for children and young people to learn and grow and educators play a critical role in what is learned and how this growth occurs.

School students attend school for a considerable period of time during their critical developmental years post early childhood through to mid-adolescence. During this period of time schools can offer many opportunities for students to be meaningfully and positively experienced through the eyes of a trusting, caring, adult; chances to develop effective, rewarding relationships with peers and adults; chances to experience consistency, dependability and safety; chances to have their concealed talents revealed and developed and chances to experience being cared about and being acknowledged.

Working as a mental health practitioner in NSW Department of Education schools where high numbers of students are deeply impacted by trauma, I recognised the significance in working to support traumatised students within the school and to support the school to support these traumatised students. I also comprehended the vital significance for the wellbeing of everyone within the school.

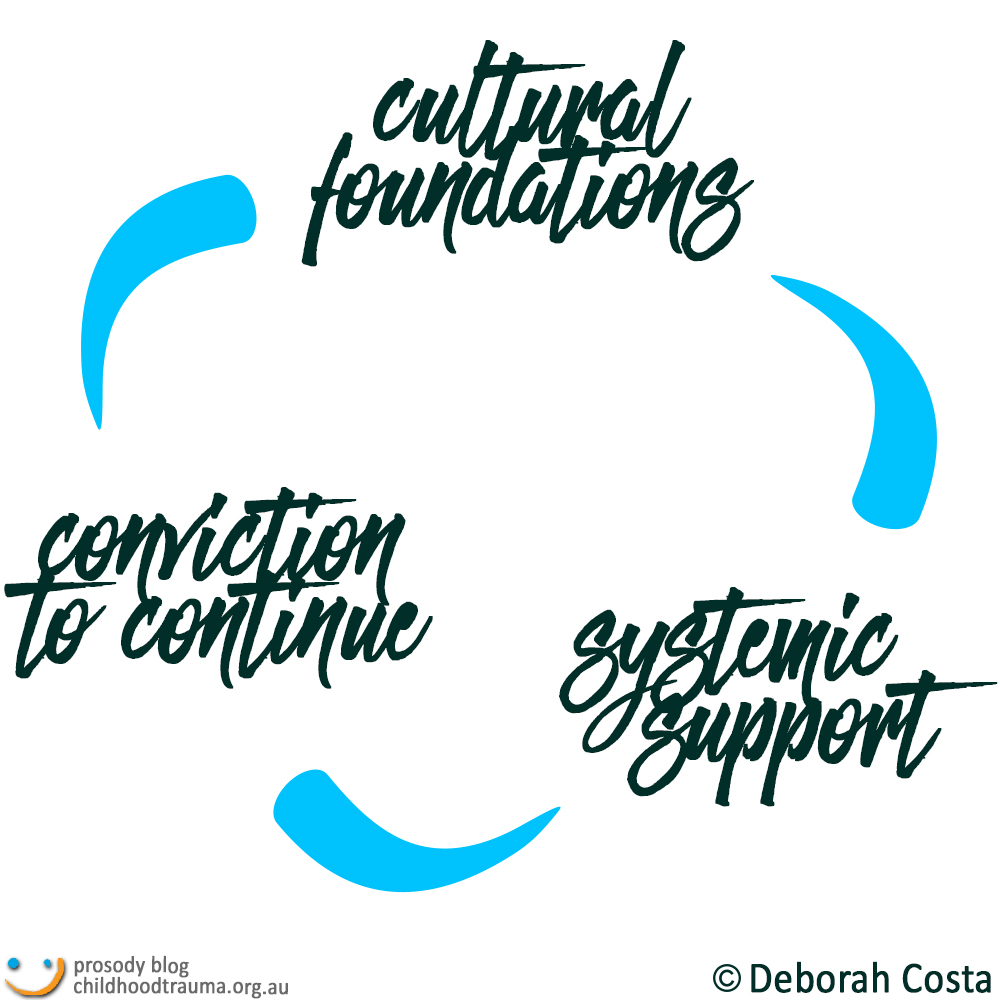

The challenges facing schools and traumatised students are wide-ranging. To achieve my goal of supporting the school to support traumatised students I formulated a plan for addressing these challenges and implementing whole of school supports. This involved three parts; first; the creation of new cultural foundations upon which to build, second; the construction of systematic models of support and, third; the conviction to continue alongside the challenges naturally inherent in working within large systems.

The challenges facing schools and traumatised students are wide-ranging. To achieve my goal of supporting the school to support traumatised students I formulated a plan for addressing these challenges and implementing whole of school supports. This involved three parts; first; the creation of new cultural foundations upon which to build, second; the construction of systematic models of support and, third; the conviction to continue alongside the challenges naturally inherent in working within large systems.

School-based Challenges

Challenges within a school’s local community inside and outside the gates contribute to the school’s culture. School’s engage in ‘meaning making’ to make sense of, and cope with, these challenges, and develop practices in response.

Some of this ‘meaning making’ is influenced by traditional ideas of childhood development, children’s behaviour and behaviour management approaches. When not trauma-informed these practices can re-traumatise students. Van Der Kolk (2014) cautions on the harm that stems from attempting to control a child’s behaviour whilst failing to address the underlying issue of abuse.

Traumatised students face the challenges of connecting and learning within school systems where there is:

- limited understanding of the impact of trauma on their development, behaviour, functioning and learning;

- unrealistic expectations of their social, emotional and cognitive abilities, and of their capacity to function successfully;

- multiple school based trauma triggers including frequent changes to routine, staff changes, other traumatised students and traditional classroom practices;

- limited resources and capacities to understand them and to meet and support their needs;

- unhelpful and harmful practices including reactive management style, exclusionary behaviour management practices and discipline approaches that can be harmful to developing relationships and connections.

Creation of new cultural foundations upon which to build

Addressing these challenges for students and educators involves whole of school shifts in the way educators:

- interact and connect with students;

- develop relationships with students;

- understand and support students;

- think about children and young people;

- understand their complexities;

- move from practices based on exclusion to practices based on inclusion;

- and, from practices based on behaviour management to practices based on relational influence. Bomber and Hughes (2013) emphasise the need for schools to shift their reliance and insistence on traditional methods and behaviourist interventions for dealing with all students towards whole school policies that include provision for individual needs and developmental vulnerabilities.

These whole of school shifts necessitate;

- continuous professional development to increase levels of trauma awareness and promote trauma informed care and practice;

- neurobiological understanding of what is happening for the students to increase understanding, empathy and connection and reduce frustration, avoidance and disconnection;

- persistent awareness raising of and advocating for each student case by case across the school to highlight the magnitude of the issue;

- and, promoting the readily available school-based trauma care resources.

Construction of systematic and whole of school models of support

Working as a trauma informed School Counsellor I was aware of the importance of whole of school approaches to supporting students impacted by trauma. Both to prevent supports from further separating out and isolating vulnerable students, and to enable those students whose lives are impacted by trauma but not known to schools, to benefit.

I came to understand the critical importance of a whole of school system for the teaching and support of development of self-regulation of emotions and behaviours in students. Van Der Kolk (2014) asserts that emotional regulation is the critical issue in managing the effects of trauma and neglect. Bomber and Huges (2013) tell us that regulation of emotions is one of the primary keys to success and therefore should be advocated for as a primary target of all interventions. Implementing the Zones of Regulation – A Curriculum Designed to foster Self-Regulation and Emotional Control (Kuypers, 2011) through the school has provided all students with explicit teaching and support of their development of self-regulation of emotions and behaviours and given the school a consistent shared language, dialogue and understanding of this area of development.

Forming a school based trauma care team including the Principal and Executive, the District School Counsellor/Psychologist and the Learning and Support Co-ordinator has empowered the process of promoting understanding and supporting of the needs of traumatised students.

Developing a model for engaging with appropriate external agencies has enabled the development of a ‘care team’ approach to supporting the student within school, ensuring, where necessary mandatory reporting in advocating for the needs of traumatised students, and encouraging longer term trauma informed care within the child’s environment outside of school, where appropriate.

Providing an approach for applying for departmental funding without the immediate need for diagnoses has enabled the school to access additional funding to implement supports without having to drive the process of obtaining a disruptive behaviour diagnosis. Van Der Kolk (2014) reminds us of the difficulties presented by these diagnoses – “Children who act out their pain are often diagnosed with ‘oppositional defiant behaviour’, ‘attachment disorder’ or ‘conduct disorder’ but these labels ignore the fact that the rage and withdrawal are only facets of a whole range of desperate attempts at survival”.

Providing an approach for applying for departmental funding without the immediate need for diagnoses has enabled the school to access additional funding to implement supports without having to drive the process of obtaining a disruptive behaviour diagnosis. Van Der Kolk (2014) reminds us of the difficulties presented by these diagnoses – “Children who act out their pain are often diagnosed with ‘oppositional defiant behaviour’, ‘attachment disorder’ or ‘conduct disorder’ but these labels ignore the fact that the rage and withdrawal are only facets of a whole range of desperate attempts at survival”.

Designing a Personalised Learning Plan model incorporating trauma informed supports has guided the school’s Learning and Support Team towards formulating necessary supports that address key areas of impairment, recognise the need for realistic and reasonable learning tasks, consider appropriate environmental variations and recognise relational supports for connection, engagement and positive outcomes.

These whole of school initiatives have advanced with changing cultural foundations.

The Conviction to Continue Alongside the Challenges

My increased knowledge, confidence and hope gained at the most recent International Childhood Trauma Conference in Melbourne, the connections formed with other professionals working within the field, observing the progress of the children being supported and the continuing process and progress in becoming a trauma informed School Counsellor, provides me with the beliefs and the assurance to continue, alongside the challenges of working to support the schools and to support the traumatised students within the schools.

Bessel Van Der Kolk (2014) tells us “The greatest hope for traumatized, abused and neglected children is to receive a good education in schools where they are seen and known, where they learn to regulate themselves, and where they can develop a sense of agency. At their best schools can function as islands of safety in a chaotic world. They can teach children how their bodies and brains work and how they can understand and deal with their emotions. Schools can play a significant role in instilling the resilience necessary to deal with the traumas of neighbourhoods or families” (pg351).

My greatest hope for traumatised students is that our schools will continue to develop the trauma conscious cultures, competencies and confidences and lead the way as educating systems in advancing recovery and growth for their students.

References:

Bomber, L.M. & Hughes, D.A. (2013) Settling to Learn – Settling Troubled Pupils to Learn: Why Relationships Matter in School, Worth Publishing Ltd, London.

Kuypers, L.M. (2011) The Zones of Regulation – A Curriculum Designed to Foster Self-Regulation & Emotional Control, Think Social Publishing.

Van Der Kolk, B (2014) The Body Keeps the Score – Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma, Penguin Group, London.