Safe and Confidential – The challenges of digital therapeutic service delivery

What does it mean to deliver therapeutic services in an online format? Delivering safety and confidentiality for clients during COVID-19 can be challenging and requires considerable thought on the part of organisations. Here the Foundation shares some of the considerations we've worked through and hope to create the opportunity for others to do the same.

This article was co-authored by Dr Joe Tucci, CEO, and Lauren Thomas, Manager Service Development at Projects both at the Australian Childhood Foundation

We work with children, young people and their families in times of upheaval for them. Times where they have experienced abuse, family violence and chronic stress. Over the decades that the Australian Childhood Foundation has existed, we have developed ways of working that have supported children to recover from their trauma and to connect with those who care for them.

Like so many organisations, COVID-19 has forced us to consider, reconceptualise and even extend our delivery of specialist therapeutic support and intervention with children, young people, families and carer households.

Our Therapeutic Services deliver work that is inherently relational, traditionally in face-to-face settings now being reshaped using digital modalities, such as texting, emails, telephone, and video-calls. Our Safeguarding Children Services have also received an unprecedented number of questions relating to how to keep children safe in the current COVID-19 emergency.

Many of our Counsellors and Therapeutic Specialists are also parents themselves, trying to support other families while being home and looking after their own. These dual roles brought enhanced empathy to both the interactions and considerations of how the move to digital service provision could impact all involved.

Many of our Counsellors and Therapeutic Specialists are also parents themselves, trying to support other families while being home and looking after their own. These dual roles brought enhanced empathy to both the interactions and considerations of how the move to digital service provision could impact all involved.

Our team have needed to produce new guidelines, documents and principles to ensure our practice remained safe and able to support the high-quality work we are accustomed to providing. This process raised specific ethical and practical considerations around privacy and confidentiality, and we felt a discussion of these might be helpful to share with this broader professional network.

Understanding the environment

The importance of the environment and its impact on therapeutic outcomes has long been a consideration. During this time of video or telephone format engagement, our Practitioners have needed to be more aware of the circumstances of each interaction with a service user in a digital format.

The privacy ordinarily afforded by having a room in which to meet the client is important when working with children and young people. The physical room provides clients with more obvious privacy and confidentiality, as well as some predictability. The need to deliver these services online created real challenges to these areas.

Alongside frameworks for privacy and confidentiality, our work involves managing and assessing risk and safety, as well as duty of care considerations. Telehealth delivery meant having to explicitly ask for information that is usually known, such as

- The location of the service user – we now need to enquire about and record this information

- Who is present in the immediate vicinity of the service user – many times, total confidentiality wasn’t possible for clients. With parents and carers also working from home, private spaces were not always possible to achieve. With this in mind, we couldn’t assume others weren’t nearby, and to understand the impact of their presence, our practitioners first needed to ask the questions.

- Who has access to the interaction between the service user and the ACF Practitioner – Since we are no longer able to physically monitor the environment in which our sessions take place, our practitioners are now asking and recording who can see the session, as well as who can hear or overhear the content.

- Enquiring as to what the service user has been doing prior to or about to do after the interaction – For all of us, but for children, in particular, the activities we engage in or anticipate impact our ability to regulate arousal. Many times, we can rely on a predictable process in the lead up to sessions – a car trip, followed by a wait in the waiting room followed by a gentle beginning to a face to face session, much of which could be tailored. With the switch to telehealth, we noticed that the start to sessions could feel more abrupt. Therapists were suddenly present in the family home, and the normal warm-up to therapy had altered. Enquiring about these activities gives all involved a sense of place, of anticipation and the opportunity to observe attention and arousal responses. It also provided useful information for ongoing risk and safety assessments.

Engaging parents and caregivers

Our practitioners, where possible, compassionately engaged adults who provide care and support to children and young people, keeping in mind that they too were likely to be juggling multiple roles. At times these adults would be present at the start and end of sessions, supporting access to the technology. Parents and caregivers were also engaged in overt conversation to assist with measures that maintain the privacy and confidentiality of the content of the interactions between ACF Practitioners and the child/young person and their important network of relationships.

Our practitioners, where possible, compassionately engaged adults who provide care and support to children and young people, keeping in mind that they too were likely to be juggling multiple roles. At times these adults would be present at the start and end of sessions, supporting access to the technology. Parents and caregivers were also engaged in overt conversation to assist with measures that maintain the privacy and confidentiality of the content of the interactions between ACF Practitioners and the child/young person and their important network of relationships.

These interactions also drive increased flexibility in service delivery. In some cases working online meant we needed to decrease the amount of direct work with children and increase the amount of parent consultation. In others, we found that direct work with children and young people was more productive and the medium supported therapeutic work in particular ways that face-to-face hadn’t. Adjusting form and format to meet the realistic restraints present for parents and carers is essential.

Choosing the most secure platforms

Choosing and using the right technology has been another area of consideration. Not just finding technology that was quick and easy to use for all involved, but also ensuring that we could meet our privacy and confidentiality requirements as service providers.

We found that we needed to investigate the various video platforms available and create a list of authorised programs that staff were able to use during interactions with our service users. These platforms differed depending on service delivery and location and were used flexibly when technological issues were faced at the service users end which we couldn’t control. All needed to be secure from outside access.

Specifically, we considered;

- Was the platform secure?

- Can we ensure sessions are not recorded by end-users?

- What internet access and reliability do our staff and clients have when at home?

- What added security features can we employ to protect service delivery?

To support the delivery of our services online, we also developed new guidelines outlining the importance of communicating with all service users and partners, ensuring that video/phone sessions/interactions were not recorded, along with modified consent procedures published as a guide for all therapeutic services run by ACF.

Broader COVID-19 related considerations for Safeguarding Children in other Organisational Settings

Over this time, the Foundation’s Safeguarding Children Services have been fielding and responding an increased number of queries around how to keep children and young people safe from harm during this time of reliance on digital communications. Organisations, just like us, have needed to revisit their policies and procedures to rapidly update them to reflect the evolving nature of service provision.

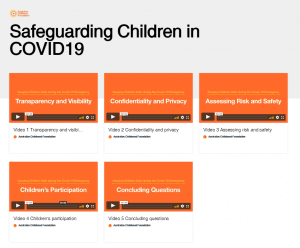

Our Safeguarding Children Services have responded to these by recommending considerations in four key areas;

- Transparency and visibility

- Confidentiality and Privacy

- Assessing Risk and Safety

- Children’s Participation

In response to the demand, the service has released five short videos covering these topics titled ‘Safeguarding Children in COVID-19’. The series is free for all organisations and individuals and you can access the videos here.

We are certain that all members of the extended professional community are grappling with similar issues and concerns. It is our hope that by sharing some of our thoughts and processes we can both support your own as well as create an opportunity for dialogue that ultimately creates safety for children and young people. There has been much that children and families have lost access to during this time, and we have been determined to ensure that our therapeutic service delivery was not added to the list.