The impact of family violence on the parent-child relationship.

We now know that the relationship between a mother and her child is directly impacted as a result of family violence. Here, Stefanie Ronzoni explores some of what is known about these impacts, as well as three steps to support mothers and children on their path to recovery.

This article was written by Stefanie Ronzoni, Senior Child Counsellor in the Australian Childhood Foundation’s Therapeutic Services.

We now know that the relationship between a mother and her child is directly impacted as a result of family violence. Family violence affects a mother’s sense of confidence in her parenting and ability to be present and available to her child in all the ways that she would have hoped for. For a child, family violence impacts their sense of safety. Their ability to trust that there are adults in the world that can keep them safe and meet their needs consistently is altered.

Hard-wired from birth

An infant is hard-wired from birth to connect and communicate with their caregiver. Through this relationship, children learn how to expect the world will be and how adults will respond to them. For a child who has been born into a safe and healthy environment that is free from significant stressors and family violence, they will likely learn that adults are safe, can meet their needs consistently and this, in turn, lays a foundation to experience the world as safe.

Impacted by violence

For those children who have early experiences of family violence, whose environments were unstable, unpredictable, unsafe and frightening, their ability to trust is severely diminished; even with their mother who is often a victim–survivor. This can lead to a distance and disconnect in the relationship between the child and their mother. This is not always obvious to someone looking into the world of this mother and child from the outside.

Disconnected in relationship

In our Therapeutic Services, we see mothers and their children who feel uncomfortable in each other’s presence as a result of the violence they have experienced. It seems they are unsure how to ‘just be’. The loss of ease can mean the mother may prefer to physically distance herself by being out of the room or place the child in childcare full time. We have noticed a strong sense of guilt and shame in the mother for the child’s experience. The experience of shame contributes further to disconnection in the relationship. Therefore, they can find ways to mask or suppress these feelings to cope and function in everyday life.

Misunderstood in community

In addition to the challenges described above, we also know that Mothers can face negative connotations and language toward them for not appearing connected, attached and attuned to their child. There can also be a lack of awareness and understanding in the community around the significant impact of family violence on the mother–child relationship.

Upon meeting one particular family, it was my experience that there was a level of discomfort in being with each other; the mother would seem to be preoccupied with doing things around the house while the child didn’t appear bothered if she was there or not. The child would then appear to act out toward the mother particularly when she was attempting to put a boundary in place. This fuelled a sense of rejection and self-doubt in the mother that she wasn’t able to parent effectively and therefore pushing them further apart, while also reinforcing messages she had received from the perpetrator of the violence.

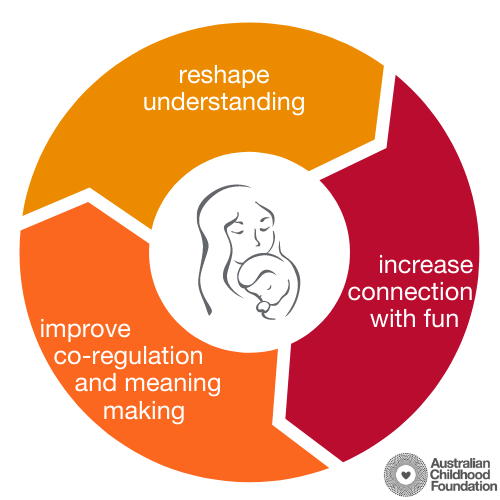

The core of recovery for younger children has three key areas:

The core of recovery for younger children has three key areas:

- Reshaping how a mother understands her child

- Supporting the child to experience the responsivity and reciprocity in the relationship in a way that is fun and playful

- Providing a platform for co-regulation and meaning–making.

The therapeutic work focuses on how to bring the mother and child back together; reattuned, re-connected, in essence, to find each other again. This happens alongside validating and normalising the mother’s experience and helping her understand that she was in a fight to survive; to protect and keep herself and her child safe.

For the family alluded to above, these shifts came about as the mother grew in confidence, trusting in knowing her child and how to respond; over time, doing so became more intuitive. In addition, the child became less vigilant to the slight shifts in her mother and they were more comfortable in each other’s presence. Mother and child found they were now able to be in the present moment and play, finding joy in each other’s company. The mother was able to prioritise time with the child, and this no longer felt as though it was something else she had to squeeze into her already busy day. As the mother grew in the ability to understand her triggers and those of her child, she also facilitated a process of meaning–making with her child about what they both had experienced.

While it may seem on the surface that this work is not quite profound, for the family and the relationship dynamic it certainly is. These smalls shifts where the child seeks out their mother, the mother’s confidence increases, the mother’s ability to be attentive and attuned to her child grows, and the mutual joy they experience in their interactions with each other flourishes; this forms the essence of recovery. It brings about a greater understanding, curiosity and openness in each other which strengthens the attachment relationship. As a Clinician, being able to observe a mother and child play, and find genuine enjoyment in each other again is a privilege, we know that it could not have occurred at a time when the mother was doing her best to survive and protect her child. These shifts and changes, all the while, re-shape and re-orient their hope-based template for the future.