Do we really put children first?

Foundation CEO, Dr Joe Tucci, has a problem with Child Protection Week. Here, he explores why he feels the week is no longer helping Australia's children.

This article was written by Dr Joe Tucci, CEO of the Australian Childhood Foundation.

I have a problem with Child Protection Week. It is important. Actually, it is vital. Starting yesterday, on Father’s Day, Australia is acknowledging its 30th such week. I have been involved in almost 25 of them as the CEO of the Australian Childhood Foundation.

Many good organisations collaborate to maximise its impact and it’s been run valiantly by the National Association for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect for all that time. But ask the average Australian when or what child protection week is and the vast majority would look at you blankly.

Ask the average Australian when or what child protection week is and the vast majority would look at you blankly.

‘Putting children first’ was front of mind when the National Child Protection Week campaign was launched in 1990, with the aim of bringing abuse and neglect out of the shadows and putting the protection of children onto the national agenda (NAPCAN, 2020). ‘Putting children first’ is also the theme in focus for the events that are to be held this week.

Sadly, it has been a set and forget strategy for successive Commonwealth Governments. No real investment, no real commitment. Just tokenism.

We say we “celebrate” child protection week now. But is that what we want? Do we want a sort of complacency that accepts that some children are always going to be damaged by violence? I don’t want that. I think we should be angry. We should be outraged. We should feel that too many children are suffering needlessly.

Child abuse and neglect involve so many different crimes against children, so much pain inflicted on them.

It includes children who are sexually abused by adults in their own family, by those who work or volunteer in institutions and by strangers who prey on children online; children beaten with fists, belts and sticks; young people sexually exploited by adults offering cash, drugs or access to pornography; children whose parents are addicted to drugs and alcohol who leave them unsupervised or unfed or in terrible conditions that jeopardise their health; children who are forced to live with dangerous threats from one adult to another in families; children who are often confronted with the fear and unpredictability of violence towards their mothers; children who are berated and verbally abused, told that they will not amount to anything, that they are stupid and unlovable; and it includes young people forced on to the streets because they are rejected by their families.

Often, children suffer different forms of abuse all at the same time.

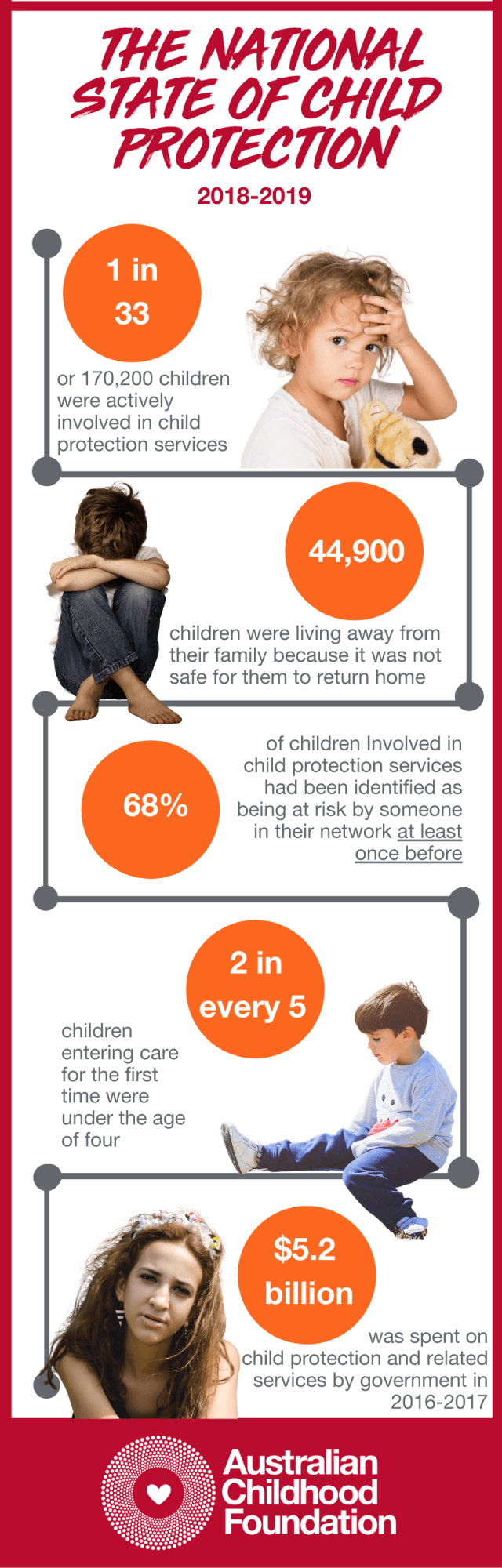

Last year, 1 in 33 children were actively involved in statutory child protection services in Australia. That equates to 170,200 children being reported, investigated or removed from their family (AIHW, 2020). More than 71,400 of these children are now on care and protection orders – up almost 4000 on the year prior. In June 2019, 44,900 children were living away from their family because it was not safe for them to return home.

Last year, 1 in 33 children were actively involved in statutory child protection services in Australia. That equates to 170,200 children being reported, investigated or removed from their family (AIHW, 2020). More than 71,400 of these children are now on care and protection orders – up almost 4000 on the year prior. In June 2019, 44,900 children were living away from their family because it was not safe for them to return home.

Just imagine Marvel Stadium at full capacity and that’s how many children live in out-of-home care.

Even more alarming is that 68% of children involved in the child protection system in 2018-19 had been identified as being at risk by someone in their network at least once before.

2 out of every 5 children put on a care and protection order for the first time in 2018-19 were under the age of four. Think about that – these are children who go to childcare and preschool.

According to a 2018 Productivity Commission Report, approximately $5.2 billion in 2016-17 was spent on child protection and related services by governments – almost $1000 per child under the age of 17 years of age in Australia. In our own research with Access Economics, the lifetime costs for the population of children reportedly abused for the first time in 2007 are $6 billion, with the burden of disease representing (a measure of lifetime costs of fear, mental anguish and pain relating to child abuse and neglect) a further $7.7 billion.

The trauma experienced as a result of abuse and neglect contributes to so many downstream consequences for young people and it often leads to problems with mental health, such as anxiety and depression.

Youth suicide is on the agenda for this government as it should be – especially now during the pandemic. But, we need to also acknowledge that child abuse and neglect can be a significant factor in a young person taking their own life. In addition, abuse-related trauma also leads to many young people engaging in crime, taking drugs and alcohol, and difficulty finishing school. We know it. The research has been clear for decades.

One week devoted to child protection is just not enough.

One week with very little resources only has the effect of distracting us from the reality of the scope and scale of the problem.

And we don’t need further distraction. Our own research shows Australians already put child abuse last on a list of community problems – after problems with roads and footpaths. They prefer to believe that child abuse happens somewhere else in someone else’s family in a neighbourhood far away – never their own.

One week is not enough. Children need more than that, much more.

The Morrison Government is making good on its commitment to tackling child sexual abuse in response to the recent Royal Commission. It is also investing heavily in strengthening our capacity to fight online child sexual abuse and exploitation which is occurring at a level that is already overwhelming law enforcement resources internationally.

But it could do more. It would not be that hard.

Firstly, we have not had a National Child Protection Council since 1991 – almost 30 years ago. It was created in response to key recommendations from one of our earliest national inquiries into violence in the community. The gravity of concern about preventing all forms of child abuse and neglect was taken so seriously that a coordinated strategy and a permanent advisory body to Government was established. If it was such an important issue back then, surely it is even more important now.

Secondly, Australia has only ever had one dedicated Minister for Children. It was Larry Anthony. He held that role between 2001 and 2004. The position was a tangible commitment to prioritising children at a federal level. Our current Prime Minister could follow the lead set by John Howard almost 20 years ago. Re-establishing a Minister for Children as a member of Cabinet would communicate a powerful message to the whole community that children need to be the focus of our attention all the time.

Not for just one week, but for every week.