Is the absence of threat the same thing as safety?

Mandy Flint explores the perception of safety in the social engagement system. Is a lack of threat equal to the experience of safety?

This article was written by Mandy Flint, Senior Training Consultant in the Australian Childhood Foundation’s Professional Education Services.

Safety is something that we talk a lot about during the Foundation’s training sessions around trauma and trauma-informed practice. Safety underpins any trauma-informed approach because if the child or young person does not feel safe then we cannot move forward with any therapeutic intervention.

A common discussion that arises around safety in training is the perception of safety. We all have a general idea of what safety means in our day to day lives but how safe we feel in any given moment will be depend on our own experiences of safety or lack thereof. This is also a topic written about on our blog by our CEO Dr Joe Tucci which you can read here.

Dr Stephen Porges (2006) who developed the Polyvagal Theory, proposes that we are all social beings and our primary goal is to socially engage. Infants, from the day they are born, need to engage their primary caregiver as a means to survive. Social cueing through facial expressiveness, crying, vocalization and sucking movements, provide poignant cues for testing out social relationships and safety. Through this social engagement, we not only get our needs met, but we bond with significant others and in turn learn about ourselves, relationships and the world around us.

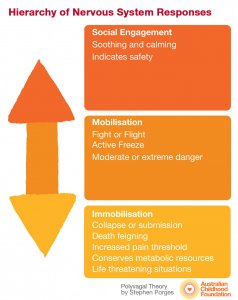

Dr Porges talks about how our nervous systems work to promote social engagement, and describes a social engagement system that is hierarchal (see diagram A); in times of safety, we are able to easily use our social engagement system to promote connection and relational attunement. In environments of abuse and neglect, however, the innate drive towards social engagement either does not work or is too dangerous to pursue, so our nervous system automatically engages our fight, flight or active freeze response in order to keep us safe. In turn, if fighting, fleeing or freezing is not an option then a third response will involuntarily engage – this involves collapsing, withdrawing or what’s described as ‘feigning death’. This response will often be seen with very young children who don’t have the option of fighting or fleeing but can also be a response for any victim of trauma.

As a result of this neuronal exercise, children who have experienced complex relational trauma will often struggle to socially engage as their nervous system is primed for threat. If a child’s nervous system has not experienced safety, then the social engagement system is bypassed in order to engage in protective survival–based responses.

Good quality social engagement, the kind that builds rapport and attunement, can only occur in safety, so for us to help the child move from a threat response to social engagement we must first establish safety. Stephen Porges discusses this in his paper Don’t talk to me now, I’m scanning for danger: where he states: “The concept of safety is relative. You and I are sitting in this room together and nothing appears to threaten us. We feel safe here, but it may not feel safe to a young woman with panic disorder. Something in this environment, which is safe for us, might trigger in her a physiological response to mobilize and defend”. (page 31)

In understanding this, one question to always ask ourselves is how does the child perceive safety? The child may not be able to articulate this cognitively, but their presentation will provide a lot of information about how safe they’re feeling. A situation that comes to mind is a carer who liked to cook a Sunday roast. For many people, a Sunday roast generally speaks to family, homeliness and tradition, but for this particular carer, they noticed that every time they cooked a roast their child began to get angry and throw things around the house. This happened on several occasions.

What the carer came to understand about this was that the smell of the roast must have been a trigger for the child. The child did not perceive the cooking of the Sunday roast as warm and homely but something unsafe. This perceived lack of safety for the child could occur in any setting or with any person – school, the doctor’s surgery, the male gardener, the female teacher.

Perception of safety is something we need to take into account in all of our interactions with the children we work with and care for. The smell of perfumes and aftershaves, the use of lighting, images and sounds, can all be potential triggers of the child’s implicit memory system, potentially engaging the threat response. We often won’t know what the trigger is unless we have a detailed history of the child, so getting to know the child is imperative in establishing what is safe for them.

Equally important is how we socially engage with the child. Our ability to be attuned to the child’s nervous system through our considered and sensitive use of eye contact, body language, posture and tone of voice can help to regulate the child threat response. In doing this we can help to build safety in a way that is meaningful for the child.

Equally important is how we socially engage with the child. Our ability to be attuned to the child’s nervous system through our considered and sensitive use of eye contact, body language, posture and tone of voice can help to regulate the child threat response. In doing this we can help to build safety in a way that is meaningful for the child.

Predictability is also key to a sense of safety: Dr Porges states: “What we often do when we’re stressed or anxious is to distract ourselves or create novelty. We’ll say, “Let’s go to the park! Let’s do something different!” But what we need to understand is that the nervous system is really requesting familiarity and predictability, which is a metaphor for safety” (Page 32).

The key message here is to not make assumptions about what is biologically safe for the child. Through awareness of our own social engagement system and being open and attuned to the child’s needs, being aware of triggers and promoting safety through predictable and consistent responses we can help build a sense of safety that opens up opportunities for rich and rewarding relationships.

Source: “Don’t talk to me now, I’m scanning for danger”: How your nervous system sabotages your ability to relate – An interview with Stephen Porges about his polyvagal theory”. By Ravi Dykema, NEXUS March/April 2006 31

You can read more about the clinical applications of Polyvagal Theory in Clinical Applications of the Polyvagal Theory: The Emergence of Polyvagal-Informed Therapies edited by Steve Porges and Deb Dana.