Can Children Really Give Consent in the Therapeutic Relationship?

‘Can Children Really Give Consent in the Therapeutic Relationship’ blog article was written by Angela Lykousis, Therapeutic Specialist in the OurSPACE NSW team, at Australian Childhood Foundation.

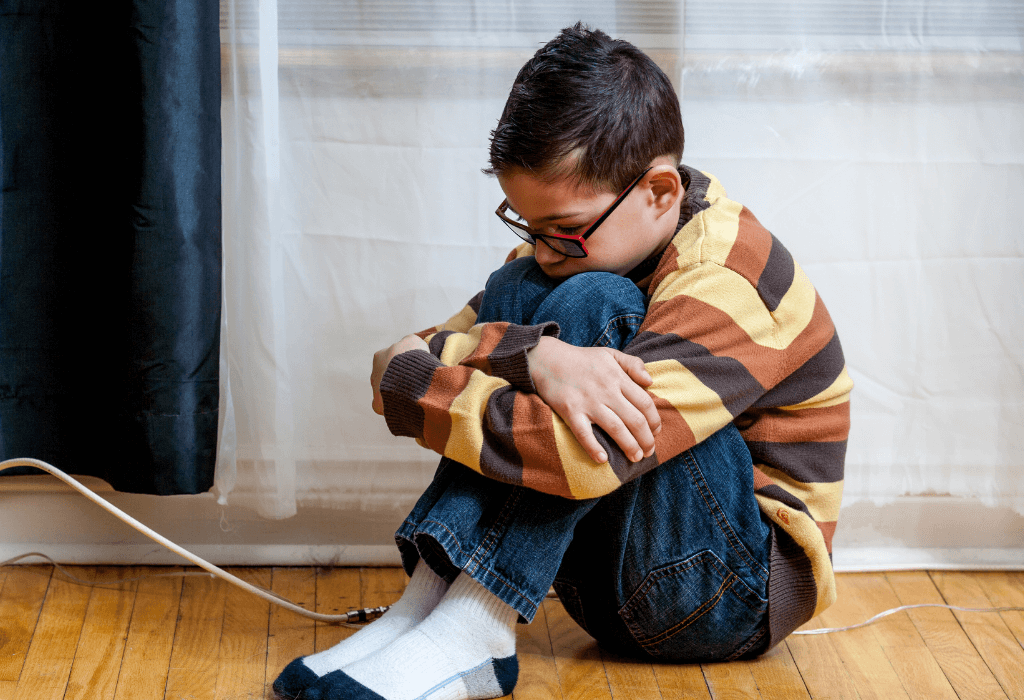

As a therapist working directly with the most vulnerable children in our community – children living in out of home care, the question of obtaining genuine consent often taunts me. These children and young people have often experienced relational based trauma within what should have been the safest place in the world to them – their family home. Abuse and neglect are often perpetuated intergenerationally by traumatised adult caregivers. These children have developed relational templates which signal warnings in a relational space.

The adults in their lives have let them down, leaving them to mistrust people around them.

These children have been removed, from their unsafe family homes, under the guise of the altruistic child protection mandate that they will be “safer” in care. As Therapeutic Specialists, it is our ethical obligation to model and provide safe working therapeutic relationships with these children and young people. Yet as I aspire to create such a space, I often find my intrapersonal dialogue sounding something like this…

What is going on here? Does this child know who I am? What am I here for? I know they’ve “consented”, but can they really say no to me? Do they know they have a choice in being here? Is this necessary? Are they here to please me or someone else? Is this child playing out their fawning instinct here with me? What are we achieving? And lastly, do they have the power to say no to me or anyone else?

The latter of these thoughts is troubling, as it presents the complexity of what many children learn to do in unsafe households. When running away, fighting or freezing doesn’t cut it, some resort to learning to adapt to an impossible situation. A fawning response becomes a subconsciously learned means of survival as children weave their way around their family dangers when a threat is perceived.

They learn to perform acts that, in their eyes, prevent or minimise the potential for discomfort, pain and hurt for themselves and possibly for others in the household. Once this trauma expression is set, it can permeate its way through to other interpersonal relationships outside the family too. In my previous professional life working in child sexual abuse jointly with police, we were trained on the concept of “interviewer bias”. This concept theorised that the power imbalance between the child and the professional can create an environment whereby the child answers questions they think will “please” the adults rather than giving honest accounts of a story. At the time, I only saw this through the lens of power, but as I complement this with a trauma lens, I can see the complexities of consent are more complex and far-reaching than a power imbalance.

I recently worked with an 8-year-old child in foster care with a “social and playful personality”. As the youngest sibling with a mother from a culturally and linguistically diverse background, whose English is limited, and a father who chose to use family violence to resolve conflict, it would appear they took on the role of “entertainer” or possibly even “distractor” in the family system. This fawning type of role became second nature for them and would have undoubtedly been joined with other responses, as I noted freezing (often noticed in the therapeutic relationship).

As sessions progressed, I began to develop an unresolved discomfort in myself. I found myself in a position as the adult therapist, feeling “awkwardly entertained” by this child before me. My body told me something wasn’t right as I froze with the same thoughts as before, playing like a broken record in my head. “Does this child know why I’m here, or that they didn’t need to be here?” I knew I needed to rethink this relationship and was grateful to have had the safe space of supervision to unpack this discomfort for what it was.

Whilst a decision was made to gently end the therapeutic relationship and instead focus more on the caregivers and the system around the child, I can’t help thinking how important our work as therapists is in attuning to the child and genuine consent in the therapeutic relationship.

So where to from here?

There are no easy answers and probably more questions raised from this experience. I’ve realised how little airtime this vital part of the therapeutic process has been given. We can always ask the child for their consent whilst being mindful of power imbalances. However, even broader than this, as therapists, when attempting to gain or revisit consent, we must see the child, in the context of their story, and remain curious about what trauma expressions are likely being carried through, both in session and in other significant relationships around them.

Interested in learning about our Trauma Informed Practice?

Knowledge about the neurobiology of child development, trauma, and attachment is invigorating practice applications across all fields involved with children and young people. Click here to learn more about applying trauma informed knowledge to improve outcomes for children, young people, their families and their communities.